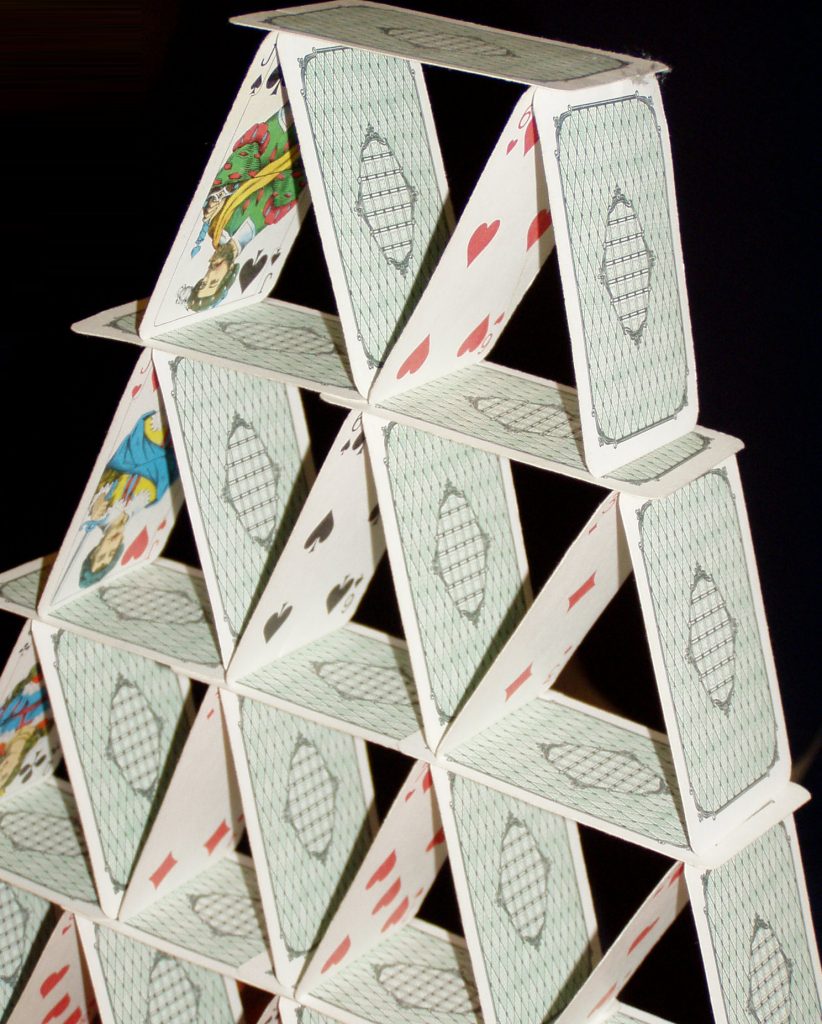

Ponzi schemes ultimately come to an end and unfortunately cause a lot of pain, suffering, and litigation. The Stanford Ponzi scheme is no exception. As demonstrated in the following case, the complex nature of such schemes demonstrates the need for excellent legal representation if you are the victim of an unscrupulous Ponzi schemer.

Ponzi schemes ultimately come to an end and unfortunately cause a lot of pain, suffering, and litigation. The Stanford Ponzi scheme is no exception. As demonstrated in the following case, the complex nature of such schemes demonstrates the need for excellent legal representation if you are the victim of an unscrupulous Ponzi schemer.

In this case, Pershing, L.L.C. (“Pershing”) sued to enjoin the (“Bevis Investors”), a group of investors who allegedly sustained losses as a result of the Stanford Ponzi scheme, from arbitrating their claims against Pershing before the Financial Industry Regulatory Authority (“FINRA”). The Stanford Ponzi scheme brought down many businesses who did not know the depths of Stanford’s dealings.

Pershing is an FINRA-regulated clearing broker that provides clearing and administrative services to financial institutions. Because of Pershing’s FINRA membership, its customers have the right to compel Pershing to arbitrate their disputes under FINRA Rule 12200. The Stanford Ponzi scheme was created by Stanford and associates where they would sell a certificate of deposits (“CDs”) that promised a fixed rate, and instead of purchasing lucrative assets, Stanford used the money to pay old investors. Stanford went on to use the money to finance a lavish lifestyle and real estate ventures. Bevis Investors allege that they purchased CDs issued by Stanford International Bank (“SIB”). Pershing executed a Clearing Agreement to provide clearing services to the Stanford Group Company (“SGC”) between 2005 and 2009. Pershing had no relationship with any other Stanford entity. Because of the Stanford Ponzi scheme, investors came to Pershing and initiated arbitration.

Pershing sued to enjoin the Bevis Investors from asserting claims in FINRA arbitration because it had no contractual relationship with them and because they could not establish such a relationship through any estoppel theory. The district court granted Pershing’s relief and Beavis Investors appealed.

The case turns on the applicability of equitable estoppel. The Supreme Court made it clear in Arthur Andersen LLP v. Carlisle that equitable-estoppel claims are matters of state contract law. The case was heard under federal law instead of Louisiana state law because it cited exclusively to federal precedent. Without an agreement or exception for arbitration, the Bevis Investors cannot force Pershing to arbitrate before FINRA. The Bevis Investors argued two exceptions permitted it to compel Pershing to arbitrate: (1) Alternative estoppel and (2) Direct-benefit estoppel.

Under a theory of alternate estoppel, Bevis Investors can compel a non-signatory to an arbitration agreement to compel an arbitration agreement to compel a signatory such agreement to arbitrate a claim in two “rare” situations. The first situation requires that the signatory (Pershing) assert a contractual claim against a non-signatory (Bevis Investors) then refuse to honor an arbitration provision contained in that contract. Pershing explicitly disclaimed any contractual relationship with the Bevis Investors and had not brought any contract-based claims against the Bevis Investors. The second situation requires that the signatory asserts a claim of “substantially interdependent and concerted misconduct by both the non-signatory and one or more of the signatories to the contract.”

Pershing had not raised allegations of substantially interdependent nor concerted misconduct by the Bevis Investors and one or more signatories to any contract. Bevis Investors also attempted to compel Pershing through direct-benefit estoppel. In order to do so, the Bevis Investors had to establish that they are party to a contract that contains an arbitration clause to which Pershing was a non-signatory, and that Pershing “embraced” this contract. Under FINRA Rule 12200, arbitration clauses are included in contracts between FINRA members and customers.

The Bevis Investors contended solely that Pershing embraced the contract between the Bevis Investors and SGC by knowingly seeking and obtaining benefits from that contract, and that Pershing is now attempting to avoid the contract’s Rule 12200 arbitration clause. Pershing neither knowingly exploited nor directly benefited from the contract at issue—actual knowledge of the contract containing the arbitration clause is needed. The case at hand demonstrates that Pershing received compensation only for its work in closing sales between the Pershing Investors and SGC. At most, Pershing indirectly benefited from the Bevis Investors’ contracts because their CD purchases prolonged the lifespan of the Stanford Ponzi scheme, enabling Pershing to clear more transactions before the scheme collapsed.

The district court’s decision was affirmed. Unfortunately for Bevis Investors, there was no contractual relationship through any estoppel theory.

Written by Berniard Law Firm Blog Writer: Michele McEvoy

Additional Berniard Law Firm Articles on Arbitration and Business Disputes: Orleans Parish Case Sent Back to Trial Court for Evidentiary Hearing over Relevant Evidence and Arbitration Clause Validity

Louisiana Personal Injury Lawyer Blog

Louisiana Personal Injury Lawyer Blog