Domestic abuse is a global issue that requires the services of excellent lawyers and even better judges to sort out the myriad of problems that arise in each domestic violence case. The justice system must use all of the tools at its disposal to try to protect victims from their tormentors while also sorting through murky and disturbing factual scenarios. The facts of these cases often make assigning blame difficult. The case of Yulia Sirenko and Martin Munger demonstrates the convoluted issues that arise in such disputes.

Domestic abuse is a global issue that requires the services of excellent lawyers and even better judges to sort out the myriad of problems that arise in each domestic violence case. The justice system must use all of the tools at its disposal to try to protect victims from their tormentors while also sorting through murky and disturbing factual scenarios. The facts of these cases often make assigning blame difficult. The case of Yulia Sirenko and Martin Munger demonstrates the convoluted issues that arise in such disputes.

It is a tragic tale that begins in Moscow, moves through Dubai, and ultimately ends up in New Orleans in front of a trial judge tasked with determining who is at fault, who is in danger, and what remedies are necessary to stop the cycle of violence that has enveloped a family that includes young children. Mr. Munger and Ms. Sirenko, a married couple, got into a fight one night in their New Orleans home. The fight left Mr. Munger with a bleeding bite on his chest. He went to an urgent care facility, called a lawyer who advised him to obtain a protective order, and then called the police. Ms. Sirenko was subsequently arrested and spent 20 days in jail. At trial, both Mr. Munger and Ms. Sirenko sought protective orders against each other. They both also sought custody of their young son. The trial court found Ms. Sirenko’s account of a pattern of abuse by Mr. Munger to be credible and granted her a protective order against him. Mr. Munger was prohibited from contacting her except in very specific circumstances relating to their son. The trial court also awarded joint custody, but with Ms. Sirenko being designated as the primary custodian. Mr. Munger’s request for a protection order, on the other hand, was denied based on the trial court’s finding that he did not meet the necessary criteria due to its determination that he was the aggressor. Mr. Munger appealed this ruling, arguing that the trial court’s credibility finding was erroneous. He argued that Ms. Sirenko was not a credible witness and that a protective order in her favor was not warranted. He also argued that the trial court erred in dismissing his petition for a protective order. The Louisiana Fourth Circuit Court of Appeal, however, rejected his assertions of error and affirmed the trial court’s ruling. It based this finding on the great deference owed to a trial court in credibility determinations and evidence examination. It found that the trial court did not err in determining that Ms. Sirenko’s account of abuse was credible.

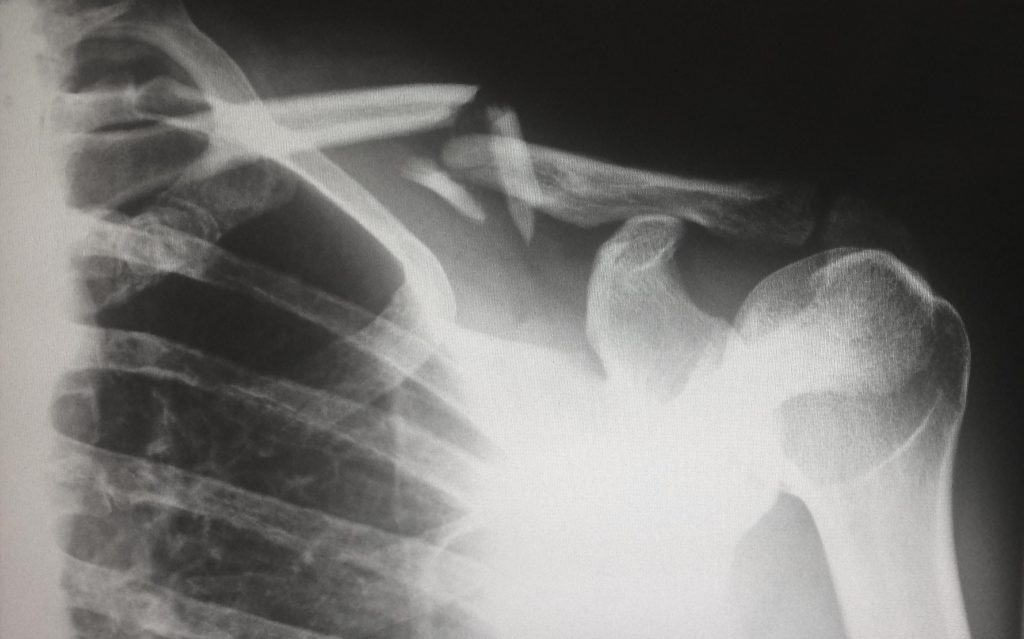

The Court of Appeal stressed that “[i]n matters of credibility, an appellate court gives great deference to the findings of the trier of fact.” Franz v. First Bank Sys., Inc., 868 So.2d 155 (La. Ct. App. 2004). This deference is owed due to the fact that the trial court gets to examine the witnesses as they are giving testimony. It gets to look at the evidence first hand. It has the best view of the evidence and “the demeanor and mannerisms of the witnesses.” The Court of Appeal simply has the record created at trial upon which it can base its rulings. Particularly in cases where conflicting testimony exists, “reasonable evaluations of credibility and reasonable inferences of fact should not be disturbed…” Stobart v. State through Dept. of Transp. And Development, 617 So.2d 880 (La. 1993). Thus, the Court of Appeal will defer to these determinations unless the determination clearly goes against the evidence presented. There was no indication of such an erroneous ruling here. The Court of Appeal pointed out how thoroughly the trial court examined the evidence and compared it with the testimony of the witnesses. The evidence of bruises and other injuries, documented in photographs, lined up with Ms. Sirenko’s testimony. The trial judge clearly explained how the evidence was linked together with that testimony. Thus, the Court of Appeal found no error in the granting of a protective order to Ms. Sirenko under Louisiana’s Domestic Abuse Assistance Act. La. R.S. 46:2131. The Court of Appeal also upheld the trial court’s decision to dismiss Mr. Munger’s protective order. The trial judge determined that Mr. Munger was the aggressor and the evidence supported that determination. Once again, the Court of Appeal deferred to the trial court’s analysis of the evidence.

Louisiana Personal Injury Lawyer Blog

Louisiana Personal Injury Lawyer Blog

Sometimes, the most complicated cases can have the most simple resolution. For West Baton Rouge plaintiffs who sued mining companies for extracting resources underneath their property without their knowledge, the ultimate outcome of the lawsuit rested on the plain meaning of statutory language.

Sometimes, the most complicated cases can have the most simple resolution. For West Baton Rouge plaintiffs who sued mining companies for extracting resources underneath their property without their knowledge, the ultimate outcome of the lawsuit rested on the plain meaning of statutory language. The statute of limitations, by definition, is the timeframe set by a state or federal legislative body in the creation of a law which governs when a party must file a claim to enforce his or her right or seek redress after injury or damage. The statute of limitations on personal injury claims varies from state to state. The standard statute of limitations for personal injury cases is three years from the day the injury or damage, in which the claim arises, took place. Mr. Landis J. Camp’s appeal from the Twenty-Fourth Judicial District Court to the Fifth Circuit Court of Appeals for the State of Louisiana against Dr. Chris J. DiGrado and Lammico Insurance Company exemplifies the vital importance of filing a personal injury claim within the statutory period of a given state.

The statute of limitations, by definition, is the timeframe set by a state or federal legislative body in the creation of a law which governs when a party must file a claim to enforce his or her right or seek redress after injury or damage. The statute of limitations on personal injury claims varies from state to state. The standard statute of limitations for personal injury cases is three years from the day the injury or damage, in which the claim arises, took place. Mr. Landis J. Camp’s appeal from the Twenty-Fourth Judicial District Court to the Fifth Circuit Court of Appeals for the State of Louisiana against Dr. Chris J. DiGrado and Lammico Insurance Company exemplifies the vital importance of filing a personal injury claim within the statutory period of a given state. Dollar stores carry a wide variety of merchandise, and stacking these items on shelves saves space. When stocking, employees should always take reasonable care to stack items in a safe manner so they do not fall off the shelf and potentially injure shoppers. For one Slidell man, however, an everyday grocery trip to Dollar General turned into a 4-year, $50,000 lawsuit.

Dollar stores carry a wide variety of merchandise, and stacking these items on shelves saves space. When stocking, employees should always take reasonable care to stack items in a safe manner so they do not fall off the shelf and potentially injure shoppers. For one Slidell man, however, an everyday grocery trip to Dollar General turned into a 4-year, $50,000 lawsuit. Medical Malpractice lawsuits can be extremely complicated and fact-specific. The general Louisiana law requires claims to be brought within one year of treatment. The Louisiana law also distinguishes liability based on intentional actions from negligent actions. The following case illustrates how in-depth a medical malpractice claim can become.

Medical Malpractice lawsuits can be extremely complicated and fact-specific. The general Louisiana law requires claims to be brought within one year of treatment. The Louisiana law also distinguishes liability based on intentional actions from negligent actions. The following case illustrates how in-depth a medical malpractice claim can become. The majority of states have what are known as “dram shop laws”. These laws address liability if someone is injured by a drunk person after consuming alcohol at an establishment. Most of these laws allow for the bar or other entity that served alcoholic beverages to be sued. Louisiana’s version of the law is quite unique, actually doing the opposite. The bar or other business must meet certain requirements to be afforded this essential immunity. The Fifth Circuit Court of Appeal in Louisiana recently considered such a situation.

The majority of states have what are known as “dram shop laws”. These laws address liability if someone is injured by a drunk person after consuming alcohol at an establishment. Most of these laws allow for the bar or other entity that served alcoholic beverages to be sued. Louisiana’s version of the law is quite unique, actually doing the opposite. The bar or other business must meet certain requirements to be afforded this essential immunity. The Fifth Circuit Court of Appeal in Louisiana recently considered such a situation.  Non-competition, or non-compete, clauses are a common part of business and employment agreements. They serve to prevent one party from taking knowledge or trade secrets to a competing business. Like any contract, these agreements are sometimes scrutinized to make sure they are actually fair to all parties. Courts will not uphold such clauses that are so limiting as to be unjust. In 2017, the Fifth Circuit of Louisiana considered such an agreement.

Non-competition, or non-compete, clauses are a common part of business and employment agreements. They serve to prevent one party from taking knowledge or trade secrets to a competing business. Like any contract, these agreements are sometimes scrutinized to make sure they are actually fair to all parties. Courts will not uphold such clauses that are so limiting as to be unjust. In 2017, the Fifth Circuit of Louisiana considered such an agreement.  If you are a homeowner, the number of security measures you take to protect your house is likely largely influenced by the safety of your area. For example, if there’s a lot of crime in the area or a lack of good lighting on your street at night, you will probably more carefully guard your home. Contrarily, if you trust your neighbors and have a vigilant neighborhood watch group, you might even feel comfortable leaving your doors unlocked. Businesses think about many of the same factors when deciding how much security their store needs. One major difference between a home and a business is that a business’s lack of security can potentially make it liable for negligence if a crime happens on their property.

If you are a homeowner, the number of security measures you take to protect your house is likely largely influenced by the safety of your area. For example, if there’s a lot of crime in the area or a lack of good lighting on your street at night, you will probably more carefully guard your home. Contrarily, if you trust your neighbors and have a vigilant neighborhood watch group, you might even feel comfortable leaving your doors unlocked. Businesses think about many of the same factors when deciding how much security their store needs. One major difference between a home and a business is that a business’s lack of security can potentially make it liable for negligence if a crime happens on their property.  It’s almost impossible to watch a movie or TV show about the police or crime without hearing the phrase “Miranda Rights.” Even if most viewers don’t know the U.S. Supreme Court case

It’s almost impossible to watch a movie or TV show about the police or crime without hearing the phrase “Miranda Rights.” Even if most viewers don’t know the U.S. Supreme Court case  The already tragic loss of a parent is only made worse when you believe that the death should have been prevented. Such was the case for Chester Domingue when his ninety-four-year-old mother, Onelia, passed away as the result of a fall in her nursing home, Camelot. While a medical provider cannot anticipate every danger that a client could encounter, what reasonable precautions does Louisiana law require to prevent as many dangers as possible?

The already tragic loss of a parent is only made worse when you believe that the death should have been prevented. Such was the case for Chester Domingue when his ninety-four-year-old mother, Onelia, passed away as the result of a fall in her nursing home, Camelot. While a medical provider cannot anticipate every danger that a client could encounter, what reasonable precautions does Louisiana law require to prevent as many dangers as possible?